Keep hearing about large language models (LLMs) such as OpenAI’s ChatGPT3.5 and GPT4, Google’s Bard and Microsoft’s Bing? Want to understand AI and even use it in your teaching but don’t know where to begin? Here’s the 101 that many academics have been asking me for, to help you harness AI’s power and utilise it more effectively!

What is a Large Language Model?

First, let’s set out what AI chatbots like GPT4 and Bard are. Each chatbot is a form of artificial intelligence known as a “large language model” (LLM). You can view it as supercharged predictive text. Given a series of words, it predicts what word is most likely to come next.

To do this, AIs are “trained” from a huge collection of text data sources such as internet books, websites, blogs, etc. to capture as much human language as possible. In the case of ChatGPT3.5 and GPT4, the training only includes text up to 2021, so it doesn’t have any knowledge or information from after this date.

Think about all the books and papers you’ve ever read, and conversations you’ve had – these influence how you think and what you’re going to say to someone in a conversation. In human terms, if you know someone well enough, you can probably predict what they will say next. This is what the AI is doing when you interact with it.

After asking the LLM a question (or prompt), they use their training to predict which words to respond with based on all the words it has seen before. During an exchange, the AI can recall what’s been said earlier in that specific chat and can use that information to guide the next prediction, making the interactions feel like a conversation. By default LLMs don’t “remember” the exchanged details between one conversation and the next; once trained, the models don’t directly update or learn from their interactions. Once the session ends, that information is no longer available to the LLM.

If you want a deeper dive, then Google’s Introduction to Generative AI is a good start.

Prompting and asking questions

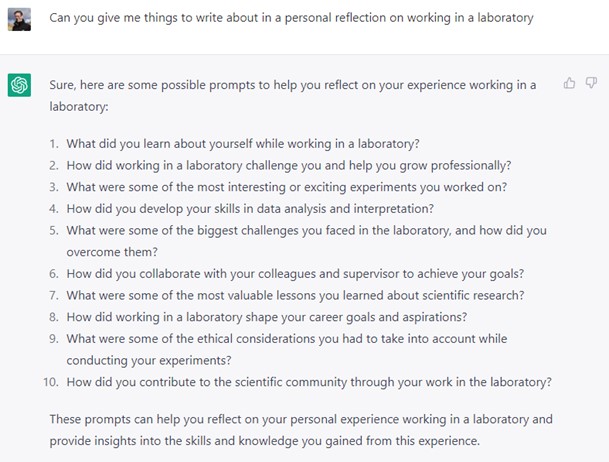

Interacting with an AI is like using a messaging app: you ask a question and the AI will respond based on the patterns it’s learned during its training. Asking a question is often referred to as ‘prompting’, and crafting effective questions is known as ‘prompt engineering’. We’ll delve deeper into that in a minute. But first, what kind of response can you expect if you ask a simple question?

Prompting can be anything from “What is the weather like today?” to “Tell me a joke” or “Explain how photosynthesis works”. Since LLMs like ChatGPT and GPT4 don’t have access to live information, they can’t tell you what the weather is like today, although AIs/plugins like Bing and Bard do have access to current information and can tell you if it’s likely to rain. If you ask it to tell you a joke without context, then it will tell you the most statistically likely joke from its training set. When prompting on subject specific knowledge, you get a response that is the most statistically likely string of words.

For the prompt, “Explain how photosynthesis works”, the AI does not actually understand photosynthesis but in its training set it will have encountered many explanations of photosynthesis, and so can generate a response that it predicts to be the most likely coherent and correct explanation.

This means that if you put the same prompt into the AI many times, you’ll generate text that’s similar in its content and structure. The results are predictable. Because it’s generating the answer from an algorithm, rather than truly understanding the topic, it can also make mistakes in its choice of words, leading to inaccuracies. This issue is less pronounced for topics that are well-represented in the training data, like fundamental knowledge and core concepts, because the model has a larger pool of information from which to draw its predictions.

Try asking the AI about a topic you know a lot about and see what is produced, then repeat for a topic you know only a little about. For the one you know well, what was missing or incorrect? For the topic you know only a little about, how could you instruct someone to verify the content?

Giving context leads to better responses

Providing context in your prompts leads to more accurate responses, as it supplies the AI with more information to work with. For instance, providing the AI with a ‘ROLE’, ‘SITUATION’ and ‘TASK’ will help guide and improve its answers.

Example: this prompt will tune the AI to create specific questions for an interview.

ROLE: You are the laboratory manager for a small biotechnology firm.

SITUATION: You are interviewing for a graduate scientist with good practical skills and teamworking.

TASK: Suggest five interview questions that could be used to select the best candidate.

In a similar way, instead of simply asking for an essay on photosynthesis, you can slightly adjust the prompt to provide more context, guiding the AI to produce an essay structure.

You are writing a 2000-word undergraduate essay for a plant biology course. Suggest a structure for the essay as well as the key content and concepts that should be covered.

Here, I have told the AI the level I want it to write at, the length and the target. This is more effective than merely requesting ‘write me an essay’, as it now provides a structure that I can explore and expand on myself. When prompting,you might need to try many iterations of the initial prompt to refine and reshape to get the desired response. For example,the essay structure might have a topic missing that you know needs to be included or a suggestion for an area you don’t need to cover. In subsequent questions, you can ask the AI to remove or expand a given area.

Asking follow-up questions in response can help you further the conversation and explore the content more deeply. For example, in my photosynthesis prompt I gained an eight-point essay plan, where point 4 talked about “Photosynthesis and Energy Transfer”. By asking the question, “Can you give me some guidance and detail on point 4 to help me understand the topic”, I am provided with more information on that specific area.

AI like GPT4 can be a powerful tool, generating text that seems remarkably human. But remember, it’s not perfect. These AI models work on stats, not on true understanding. So, while they can write text on almost any subject, sometimes they might go off topic or use incorrect ideas. They might make a mistake, miss a nuance or even create something that just doesn’t make sense. You have to be the one checking that the AI is on track, making sense and not stepping over any lines.

Now try crafting your first prompt by giving a role, situation and task and see how it changes. Or ask it to draft an essay plan.

Putting new information into the AI

One of the latest enhancements to GPT4 includes plugins that allow direct uploading of files, such as PDFs. Alternatively, you can manually input a body of text and signal the AI to process it, typically by prefacing it with a command like ‘READ’. This command signifies to the AI that the following text should be absorbed and used to guide subsequent responses.

For instance, you might say, “I am going to provide a body of text for you to process. Please read this text and confirm you’ve done so by responding with the word READ.” Once the text is introduced, you can then guide the AI’s use of that information with further prompts. So, if you’ve input the main body of an essay you’ve written, you could use follow-up prompts to instruct the AI, such as:

“Provide a short summary of the information in an abstract style”.

“Reword for clarity and remove redundancy in the text”.

“What are the key points of this text?”.

However, keep in mind that the AI can only use this new information for the duration of the current conversation. It does not ‘learn’ or retain this information for future conversations. Also, be mindful of ethical considerations when inputting personal or sensitive information.

Take a block of text and place in in the square brackets in the prompt below, then ask the AI to summarise, reword or change the text in some way.

“Please read this block of text, when you have read it say READ and wait for the next prompt [YOUR TEXT HERE]”

Adopting personas and having structured conversations

By crafting your prompts, you can instruct the AI to adopt a particular persona or respond in a specific style. Fun examples of this are to have the AI act as if it was a well-known person or to respond in a given manner for instance, as an academic.

“Take on the persona of the Guide from “The Hitchhikers Guide to the Galaxy” – we are going to have a conversation as if I was an intergalactic traveller to earth, are you ready?”

The AI can now converse with me in using that voice. A more academically related prompt might be:

“You are a University Professor writing a module descriptor for a new course, help me write the learning outcomes.”

These prompts can be expanded to include instructions on how the conversation will develop and the direction that it might take. In this example, direct instructions are given to the AI about the way I want it to respond:

“Your role in this conversation is to act as a personal tutor. You are taking on the persona of a University Professor. You will ask a simple question to start with and, if the response is correct, ask increasingly more complex questions. If the question is answered incorrectly, you will provide feedback and hints to help answer the question. Your questioning will be set at undergraduate levels of understanding.

The topic of conversation will be [your topic here].

When you are ready, ask your first question.”

Such a prompt works well on fundamental knowledge topics of established processes that are well represented in the training set. Other ideas might be to write a prompt that guides students through reflective writing or choosing the correct statistical models.

Try writing a prompt to ask the AI to behave in a given way or take on the persona of your favourite character.

Summary

Harnessing the power of AI, particularly large language models (LLMs), like OpenAI’s GPT4, Google’s Bard and Microsoft’s Bing, can benefit your teaching. By using the tips in this 101, you’ll be able to get started with prompt writing and interact with/use AIs in your practice. The next stage is to consider how you can use this with your students as a tool for learning, and develop both your and their digital skills. One of the best ways to learn is to do, so get stuck in and experiment!

Thanks to this post’s co-author, Mel Green, for her input and editing.

AI 101 – a short guide to good prompts by David Smith is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

A key advantage of MCQs is that they are easy to mark giving the opportunity for instant feedback and can act as a useful learning tool. Blackboard quizzes, as well as

A key advantage of MCQs is that they are easy to mark giving the opportunity for instant feedback and can act as a useful learning tool. Blackboard quizzes, as well as